I will never experience the sensation of freefalling, described as the ‘long, lonely leap’ by Joseph Kittinger, US Air Force captain, as he stepped into space from a balloon 31 333 metres above earth in August 1960. I cannot even step aboard a plane without a sense of dread or look down from great heights without vertigo. It is incredible to me, therefore, that Albert Eastwood, my maternal grandfather’s first cousin, was once described by the press as the ‘king of the air’.

In 1904, Albert left the orphanage at Nudgee he was raised in, being discharged at last from the State's control, and joined the Beebe Balloon Company, run by the American Vincent Beebe. In his own words, Albert was keen to ‘see the world’. The Spaniard Christopher Sebphe, the Austrian Zahn Rinaldo, Albert and the occasional ‘sky-scraper’ Roma Villiers parachuted from enormous hot-air balloons entertaining large crowds at fairs and festivals across Australia and New Zealand, from the large cities to the tiniest of country towns, and farther afield to India and Java. They were renowned for their showmanship, their performance described as ‘the most hair-raising act ever seen’.

Rising rapidly in their balloons, usually to 1500 to 1800 metres but sometimes as high as 2400 metres above the earth, the parachutists would perform feats such as hanging upside down, suspended from one leg on a single trapeze. At Beebe’s signal, usually a pistol shot, the bar would drop away and they would spiral towards the ground in a patriotic triple jump, releasing first a red, then a white and finally a blue parachute.

Companies frequently sponsored the balloon company to perform at the fairs to promote products as ‘O.T. chilli’, a type of stimulating cordial, or Terai or Viceroy teas. Snake charmers, fireworks, magicians and the ‘cloud climbers’ for just the price of a pound of tea (or a half-pound for a child) or a bottle of O.T., as the faithful would be rewarded by being admitted to the fair for free on presentation of an empty tea packet or bottle top.

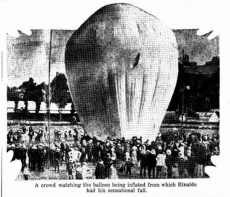

The fairs brought the world to people’s doors, even in the most out-of-the-way places, giving people a glimpse of how humans might shake free of the earth to journey thousands of metres into the clear still blue, the balloons a huge and lumbering prototype of this future – one that required a fitting level of exertion to realise. An almost fearful crowd referred to the 25-metre-high balloons as ‘monsters’, after watching them being laboriously and dangerously inflated. Beebe raced about shouting instructions and reputedly brandishing his pistol to keep control of the young lads who had been tempted by glory – and small change – into the unenviable task of holding the balloon steady over the fire while it was being inflated. Not an insignificant danger, as gasoline was used to ignite the wood set in a trench under the balloon.

Albert was thought to take these proceedings in his stride, as one reporter suggested in 1909: ‘Puffing a cigarette with consummate ease as he lay roped to the parachutes, he watched the colossal ball absorbing the gas until the signal should be given to be off’. However, just a few years but a whole lot of experience later, Albert described the moment when he was launched from the earth differently, as a ‘terrible strain on the nerves, and you wonder as hard as you can in the time there is available, and it is only a second or two, whether you are ever going to steady, and whether you have seen the last of the earth as a live spectator. The rush away, particularly when you flash across the flaming furnace, is nerve-racking until you get used to it’.

His laconic approach was never so evident as the time when he was parachuting in Java and a volunteer, a young Javanese man, who was holding the balloon while it was being inflated, failed to unravel the cord from his hand in time and shot up in the air with the balloon. Albert remained unaware of what had happened until he heard the crowd ‘shouting excitedly’ at him. His initial thought was that something had gone wrong with the balloon, but it continued to rise steadily. Albert looked around to finally see the terrified man hanging onto the balloon, desperately trying to reach him and shrieking all the while. Albert managed to grab the man and calm him enough to attach him to his chute, many long moments later landing them both safely on the ground. He said, in his usual understated way, of his reluctant passenger that ‘he had been through an experience that he would never care to endure again’. The white community in Java were apparently so taken with Eastwood’s rescue that they pitched in to buy him a present.

A correspondent for the Perth Daily News interviewing Albert and Christopher Sebphe in 1910 clearly felt frustrated by their inability to articulate how it felt ‘to soar and fly and engage generally in the conquest of the air, which presently all of us will have to take on when balloons and aeroplanes and airships of all sorts become common as tram-cars, railway trains and hansom-cabs’. So he focused instead on their appearance. Eastwood was described as running ‘more to prettiness in appearance’ with ‘hair that curls itself, and is dark. Also, he has eyes which talk, and a face which is smooth and attractive. Still he has that about him, evidence of latent strength, which Sebphe lacks’.

Short at only 5 foot 4 inches (1.6 metres), like my grandfather, Albert was often described as handsome, but as ‘Franziska’ wrote in her column for the same newspaper, it was Eastwood’s daring that made him ‘appeal peculiarly to the fair sex. His performances give them an emotional thrill which moves them to the depths. When he returns to earth, the men rush up in thousands to cheer and chair him, but the girls shyly ask permission to kiss him’. The balloon boys were truly it, as their advertising suggested. The great Rinaldo discovered this after he drifted from the Exhibition Grounds in Melbourne to land on a rooftop in Collingwood in 1908 where he was mobbed by a group of young women desperate to cut locks of his hair.

Melbourne was to prove unlucky for Rinaldo. After his balloon began to deflate via a small rent in the material soon after ascent from the Exhibition Building grounds in 1913, he was dragged by high winds straight through a top-storey window of a terrace house in Faraday Street, Carlton. Before he could jump off the trapeze, the balloon jerked back, taking him straight back out the smashed window and dropping him 6 metres below on the footpath. Anaesthesia was fortunately administered as he was patched up at St Vincents Hospital.

Bad landings were common; the balloons were impossible to control and frequently drifted towards oceans and rivers, buildings or roads, railway or telegraph lines, or much worse, electricity wires. To give a prime view to the waiting crowd at the Australian Natives Association exhibition in Melbourne in February 1910, Sebphe and Albert jumped while the balloon hovered over nearby Nicholson Street. Sebphe landed safely in the grounds, while Albert sailed over Nicholson Street and into a lane off Hanover Street in Fitzroy, falling in what a newspaper described as a ‘rather difficult place’, his parachute catching on a ’20 foot pipe ventilator which towered over a portion of the house’ and bringing Albert smack-bang against its side brick wall. He escaped without injury and returned to the grounds to a hearty welcome.

In Launceston one month later the welcome was less hearty and more stunned, as after performing a range of stunts on the trapeze suspended from the balloon, Albert jumped from 1500 metres, his first parachute opening, and then his second, and then – a gasp from below– the crowd froze as his third chute failed to open, its ropes tangled, and Albert came smacking down to earth among the hundreds of spectators on East Launceston hill, lying still and silent as death. The crowd rushed to him, fearing the worst, but he rose up, badly bruised, one leg damaged, to return victorious to the showgrounds before being taken to hospital to begin his slow recovery. Describing his first jumps immediately after the fall, he said ‘I thought of home and mother, and believed I was done for. But once the parachute opens the rest is easy; and all you have to do is to keep your eyes open for a safe place to land. You can, if you are wary, kick yourself free of a dangerous spire or gaping chimney stack, but you sometimes can’t dodge a roof or a tree, and you have to take your chance and make the best of it’.

Being dunked in a river was not unknown, as Albert discovered that year in Christchurch in New Zealand, having fallen into the Waimakariri at its mouth and barely escaping being washed out to sea. He returned to the fairgrounds covered in slime and mud, minus balloon and parachutes. This perhaps dampened the ardour of the female onlookers but apparently left his spirit for ballooning undiminished.

He was similarly fortunate in 1914 when he jumped from the Domain Cricket Ground in Auckland, only to drift into strong air currents that took him ‘perilously near the sea’, according to an account in the Auckland Star, but instead deposited him a mile or so away, startling the occupier of a house in Parnell, who looked up to see the tiny airman ‘float gracefully down into the back yard, and, after breaking a clothes line in the course of his fall, safely reach terra firma again’.

The chutes were prone to not opening. In a spectacular race to the ground with the great Rinaldo at the Jubilee Oval in Adelaide in 1910, the lighter Eastwood cut away from the balloon at nearly 1400 metres, leaving Rinaldo to rise another 150 metres before launching himself into the race only to find that, at 2500 feet, his tricolor parachute failed to open leaving him to make what a journalist described as a ‘terribly rapid flight for the rest of the journey’. The crowd was horrified, convinced that he would die. Rinaldo fell into the hard embrace of a waiting fig tree in the grounds of Mrs Bertel’s Quambi nursing and rest home in North Adelaide before bouncing onto the ground less than a yard away from a baby in a cot and a few yards from a woman reading in the grounds, almost scaring her out of her wits. Rinaldo apparently remained calm, telling spectators ‘I’ve had worse bumps than that’. After reassuring the crowd that Rinaldo was alive, Albert made light of the fall: 'Why,' he said, 'what's wrong with landing at a hospital. I struck a worse place once – a cemetery – and was laid out for half an hour.'

As a sideline during these glory days, Albert represented Beebe’s Polite Vaudeville and Minstrel Company, which toured Australia and New Zealand from 1910 onwards to much acclaim. Billed as offering ‘clean comedy, bright and catchy musical numbers, and clever specialty acts’, it was apparently a night’s entertainment of the likes not seen before in the Commonwealth, drawing on the talents of international and homegrown stars. Albert must have been having the time of his life – until, like many men of his generation, time suddenly ran out.

By 1914, not long after his descent into the clothesline in Auckland, Albert was on a ship to Egypt, having joined up with the Canterbury Mounted Rifles in New Zealand to go to war. His nephew Frank Tyrril has written in a family history that Albert flew spotter balloons during the war, but I'm yet to find evidence to suggest that he spent his war anywhere other than firmly on the ground. After serving in Gallipoli, Europe and Egypt as a gunner and briefly as a cook, he returned in 1919 to begin parachuting from planes, one of the first to do so in Australia and the first in New Zealand. He used his triple red, white and blue rig and trapeze, which had proved so popular in balloon jumping, a method the air force and Department of Defence highly disapproved of at the time due to the risk to both pilot and parachutist. The parachutes, as we know, were frequently unreliable, the ropes easily tangled, and Albert had to get from the cockpit to the tip of the wing before cutting away from the plane – an extreme sport in itself. In 1923 during jumps in New Zealand, reporters described how he walked carefully out along the three-inch three-ply platform along the bottom plane of the left wing of an Avro seaplane to his waiting rig, the pilot skillfully keeping the plane from rocking with the extra weight on the wing. In Auckland he launched himself from 1400 metres with the plane travelling at 140 kilometres an hour falling nose to the ground for hundreds of metres before he opened his red chute. He made ‘a perfect landing’, according to Albert, the only damage a large rent in his trousers.

Four long years of war had not diminished his appetite for death-defying action and had shown him that balloons had already been consigned to a slower-moving past, and that the future lay with planes – an infinitely faster, more sophisticated, future that required even more spectacular feats to impress the crowds.

Albert died in Brisbane in 1961 having made it to 74 years of age, perhaps his greatest feat, given his daredevil life. He died in obscurity and alone, apparently having never married or had children, and having little contact with family. He moved house frequently, doing odd jobs and training and racing greyhounds. My mother occasionally referred to him as the ‘mad balloonist from Queensland’, and his story stuck quietly in my mind, occasionally surfacing to remind me of a more credulous time, when the skies were empty and you could be shocked and awed for just the price of a packet of tea or a bottle top.

I like to think of Albert, perched below his gigantic balloon on a trapeze high above the ground, cracking jokes and bravely tempting fate, waiting for Beebe’s pistol shot before letting himself drop away. Of the fall before the parachute unfurled, Albert said 'It's a beautiful sensation. Better than motoring or swinging easy.'