‘But was she murdered?’, I asked. The sergeant sounded puzzled at my question. I explained that my family had never been certain about how she had died; the coroner’s inquest had returned an open finding. A split-second’s silence at the other end of the phone, before he responded. Murdered. Yes, there seemed little doubt. He was patient but direct, as if explaining the situation to a child.

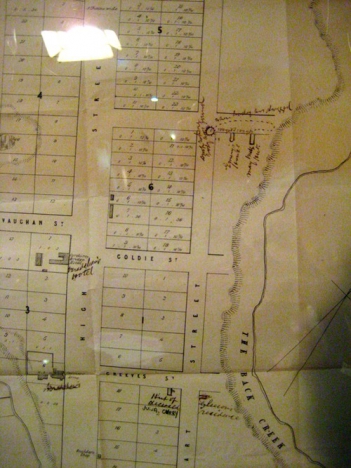

He sounded busy, his job here done, so we arranged a visit to the Police Museum in Melbourne, where I could view the map of the crime scene made by the police in 1886. Murdered. I hung up the phone, surprised at the ease with which something my family had always suspected had suddenly become real.

I had been searching for information for a while about Julia Curry (nee Gleeson), my great-great-grandmother, unable to shake off the image of her lying dead in a ditch, her neck broken, a shawl neatly shrouding her body, on a dark lane at the edge of a tiny village once called Corduroy Bridge and later Clarendon in western Victoria, sheltering close to the oddly shaped extinct volcano of Mt Buninyong.

Julia died some time between 2 and 4 November 1886 from a dislocated neck. She was somewhere between 54 and 66 years old, depending on which account you believe, and was a widow. She lived alone in a small hut at the edge of the village and scrubbed floors at the schoolhouse to get by.

She’d come from one harsh life to another. Born in Ireland, Julia arrived in Australia from County Clare probably around the 1850s and with the help of assisted passage, chased out of Ireland by sickening poverty. The first record of her in Australia is her marriage in Geelong to John Curry in 1857, she a servant and John a labourer. Less than a decade later, the Currys (or Curries) turn up in Clarendon, with John purchasing a small allotment of land.

Typing her name into Google when I had a free moment, I would mostly come up with articles from newspapers at the time – ‘Suspected outrage and murder’ or the more equivocal ‘Mysterious death of a woman at Clarendon’ or ‘A suspicious case’ – until the time when I noticed on a blog of a tourist who had visited the Police Museum a description of the map and the crime. ‘An early CSI!’, she called it. I had called the sergeant at the museum immediately. It was the first true lead I had.

I had begun to really like this woman; she had a taint of independence and whiff of scandal about her. It seems likely that she and John, her husband, had separated; she stayed on in Clarendon, while he went north, dying alone six years before Julia’s death on Poon Boon station near Balranald. She obviously wasn’t one to shy away from a blue, her brother Patrick admitting at the coroner’s inquest that they hadn’t spoken for a few years, an astonishing feat given that they lived over the lane from each other. And she clearly wasn’t one to shy away from a drink; her liking for hard liquor featured in the witness statements at the inquest, as it apparently did in her friendship with Mrs Brady, the chief murder suspect, Julia’s son describing how they were ‘in and out of each other’s houses’.

I started to talk about Julia too often with friends, trying to make sense of the evidence and piece together what had happened. They bought me a Trixie Belden book for my birthday and teased me about my cold, cold case – so cold it was Arctic.

According to the statements to the inquest, conducted by coroner James Augustus Mulligan and sworn by ‘good and lawful men of Clarendon’, Julia’s body was discovered at 5am on 4 November by her brother Patrick Gleeson, returning home from a paddock ‘some distance’ from his house. He describes how ‘evenly and smoothly’ the shawl covering Julia’s body and face had been placed. Patrick called for help, conscripting the nearby Emery family. Patrick followed the track that ended just before the house of Mary Ann Brady, the neighbour, conveniently looking as if it had been made by a body.

Patrick then sent young Isaac Emery to Buninyong to inform the police. In a strange coincidence, according to his statement to the inquest, William Graham also happened upon Julia’s body at exactly the same time as Patrick and found the very same track to Mrs Brady’s house, only he suggested that the track looked as if it could have been made by a log. By the time Isaac made his statement, the details were familiar – rehearsed even – but he added one vital clue: the track didn’t stop at Mrs Brady’s house but continued past it to a panel in the fence near the creek, but he failed to notice if it goes further.

Julia’s youngest son, Michael Gleeson, then 17, had been to her house on the evening of the 2nd and again on the following night, but she was not home. He stayed over at her place alone on the night of the 4th and was woken at one in the morning by footsteps on the stones outside and a knock on the door. Who goes there?

The sergeant who initially investigated her death was called out to Clarendon from Buninyong on the morning she was found. He decided that the circumstances warranted an inquest and cast suspicion on a neighbour, Mrs Brady, suggesting that Julia’s body had been dragged from Mrs Brady’s house and placed in the ditch on Cathcart Street. Julia’s injuries – the broken neck and bruising to her face – were, apparently, the result of falling out of a high bunk-bed at Mrs Brady’s place. Easy to do when you supposedly have a gut full of whisky. Keen to hide this fact, Mrs Brady, herself well past middle age, supposedly dragged my great-great grandmother nearly 300 metres up a slope to her final resting place, then covered her body and face with the shawl. Hard to do when you supposedly have a gut full of whisky and you’re lugging a body with you.

Early one bitterly cold morning, my mother and I stood in front of the display case at the Police Museum in the city, peering at the map of the neat village and the careful annotations of the murder scene, including, of course, the local pub. The light from the room reflected in the glass, making it hard to read the map, so my mother kept shifting around, wobbling slightly, her balance bad and her arthritic knee aching, to get a better view. I traced the so-called path of the body, trying not to giggle – it would have seemed inappropriate – at the earnest but completely inept attempt to record the murder scene, and trying to imagine myself into it, stuck with the obvious question of why would anyone think that it was a good idea to drag a body back and forth up a solid incline in the middle of the night, if the story about Mrs Brady were true.

Shame surrounded Julia in death, as it could well have in life. Doctor Hardy told the inquest that her stomach contained partly digested food and smelt of an alcoholic spirit, most likely whisky. He found that her injuries – a bruise on her right temple, an older bruise on her arm and the dislocated neck – were more likely caused by a drunken fall than criminal assault. And the fact that her dress was up around her knees was probably due to the fact that she had been dragged by her feet. The dragging also apparently explained why she had soil on her back, buttocks and hair, as well as her skirts (undergarments?) and dress. Would the fact that she was naked at some point not give you pause for thought? At last, he got to the point: ‘From the state of the organs of the deceased, I should say she was of intemperate habits’.

I read his statement and all I could see is that he proved that Julia was likely a drunk, not that she hadn’t been murdered. Yet her being a drunk was contradicted by her brother Patrick, a local selector and upstanding citizen of the local community, father of a son later to become a priest. Although, on his own admission, he had not been on speaking terms with his sister for the past few years, he still thought that she was ‘generally sober but occasionally had a glass of liquor in her own house’. Julia’s son Michael, however, showed less restraint, plainly stating to the coroner that his mother ‘got drunk sometimes’.

So much energy expended on discussing her drinking and so little on examining the witness statements, the many repetitions and numerous inconsistencies already described and to which I add that William Page, the police constable who investigated her death, described her clothes as being ‘up to her hips’, which is just a bit higher than her knees Dr Hardy, and suggested that the entire right side of her face was discoloured – no small bruise on her temple. He also mentioned how her left leg was doubled under her right. A break perhaps?

So picture the scene. It’s the late 1800s. You and your friend are drunk. She stays over. At some point during the night, she drunkenly tumbles out of her bunk, snaps her neck on your floor and dies. What do you do? Leave her on the floor and run for help? You are innocent after all; it was just an accident. Or panic, drag the body out of your house, presumably naked, first downhill towards the creek and then back up hill, to leave her in a ditch near your place and then carefully shroud her body. Hmmm.

Mrs Brady denied all knowledge of the murder. In her version of events, she repeatedly insisted that she hadn’t seen Julia since 30 October and that Julia hadn’t been to her house since before winter. When Patrick had pointed out the track from near her house, she wondered if it had been made by a slide that the Emerys used to carry water from the creek. And then the clincher. You can almost hear the voice of the sergeant demanding ‘Were you drunk Mrs Brady?’ as she insists in her statement ‘I was quite sober on Tuesday [2nd] and Wednesday [3rd] last’.

After listening to nine witness statements, coroner Mulligan stated the cause of death as ‘dislocation of the neck but how this occurred there is no evidence to show’.

Julia was buried in the Clarendon cemetery out of town in an unmarked grave (number 112), which we have yet to find. On her brother Patrick’s grave, a plaque has been added more recently, remembering Johanna Gorman and her children, of whom Julia is supposedly one, although all evidence we have suggests that Julia’s parents were Ann and Patrick Gleeson.

I went with my parents to Clarendon this year to search for … what? Evidence? Some kind of sign? Turning off the highway, dead ahead, where Patrick’s house was marked on the map, was a tumbledown old cottage, modest at front but quite large once you counted all the extensions at the back. It was closed up and the yard was cluttered with broken-down cars and truck. It was definitely of the right era: Patrick’s cottage? Which meant that the ugly modern brick villa behind us was where Julia’s hut once stood, right over the lane from her brother’s.

I walked up what once was Cathcart Street, now just a grassy path between farmland and the backs of houses, in what was once quite a thriving small village, which later, forsaken by the railway line to Ballarat, began to die, and now was just a collection of houses and an old Catholic church on the busy Midland Highway. Standing at the spot where she had been murdered, my parents dozing in the warm car at the end of the lane, I tried to enter Julia’s life, re-creating her journey from Ireland (did she come with family or alone?) to Geelong and on to this tiny out-of-the-way place under the strange volcano. A life no doubt of domestic service and scrubbing floors, her husband’s claim to a small parcel of land in the new country clearly doing nothing to advance her status. A migrant’s life. A woman’s life of the times. Did she occasionally go to Buninyong? Take tea in the lovely tea-rooms? Attend dances? Laugh off the hardships of life with friends? Or did she sit lonely in her dark hut at the edge of town, glaring over at her brother’s cottage, warmed only by whisky.

I stood by the old stone fence and peered down what I thought would have been the track to Mrs Brady’s and the Emerys’ and tried to imagine dragging a body – even that of a small woman, if she was – up that hill. I’m strong and tall and don't mind a challenge, but I realised that there’s no way Mrs Brady could have done it, at least not alone. None of it makes any sense. What happened in that town when they all woke up on 6 November after the inquest was over? Did Patrick return to his farm, Mrs Brady to her whisky, Dr Hardy to his moralising? What of Julia's children? Did any of them pause to remember her for just a moment at the end of the lane where she died. or did they hurry past, heads down, Julia’s murder just another ugly brutal death, unremarked and forgotten, in a harsh country?

A warm and gusty wind stirred up dust along the lane and, in the background, was the monotonous drone of a ride-on mower. I inhaled the sweet-sour scent of freshly cut grass and leant against the fence, its stones cold and hard and comforting. The sky was dark; a storm was on its way. It seemed fitting.